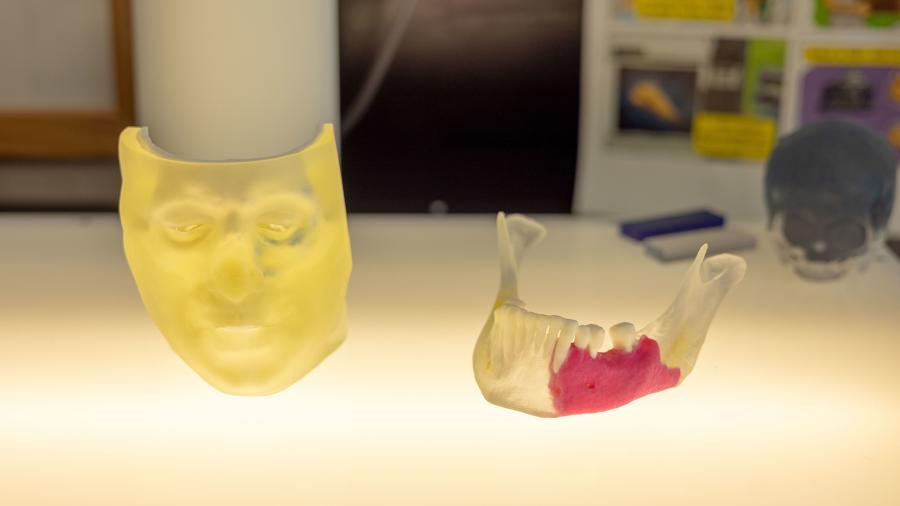

On the fourth floor of the Minneapolis Veterans Administration Medical Center, with a panoramic view of the Mississippi River valley, an office countertop holds a seemingly macabre collection of plastic models: A foot, hand and forearm, a heart, part of a spine, a lower jaw and other small, novel devices.

To the visitor, they’re just that. To their creator, Drew Davis, a 2007 UW-Stout engineering technology graduate, they are so much more. The 3D-printed models are re-creations of actual body parts of veterans, based on their MRIs and CT scans, that support their treatment and potentially improve their lives.

Davis and the VA’s RECOVER team — Rehabilitation and Engineering Center for Optimizing Veteran Engagement and Reintegration — give hope to veterans.

The collection in the high-tech, 3D print lab includes, for example: one veteran’s aorta 3D-printed in exact detail that a doctor used to explain what had to be fixed; a half-scale head with a face that can be peeled away to reveal the extent of damaged bone. Davis uses software that takes CT and MRI data, captured by a radiologist, and generates 3D printable files of patient anatomy. He then optimizes the 3D printer settings to print bone and tissue structures.

The foot on the counter is part of an ankle-foot system designed for veterans with a prosthesis. The system is attached to the wearer at the end of the prosthetic socket. It slips into a 3D printed foot that is designed for a specific heel height.

The veteran can bring in a pair of shoes and walk away with a prosthetic foot for that shoe, which slips onto the ankle unit. Imagine a veteran walking into their home, taking off their outside shoes — foot included — and putting on their inside shoes, foot and all.

At RECOVER, veterans are included in the design process, whether it’s a novel design or adaptive technology. “We take their input and make it real. Helping the veterans makes the job worth it,” Davis said.

Davis also has designed a system to test the strength and wear of a prosthetic socket, creating a pneumatic testing frame and using custom software to control the tests. “The goal is to come up with a test that can confirm the structural integrity of a traditionally fabricated socket. We can then apply those same tests to start to optimize materials and design of the sockets,” he said.

A wheelchair that makes veterans more mobile

On another floor at the VA hospital, Davis enters a windowless room with an assortment of wheelchairs. One of them is special: A prototype of a manual, mobile, standing wheelchair. Davis sits down, presses a button at the end of an arm with his thumb and the chair slowly rises to a standing position.

Then, he rolls forward like he wants to get something from a high shelf. Think of the many more things people in wheelchairs could do if they could move and stand. “It would help empower veterans,” he said.

Davis, who has worked at the VA for more than two years, helped design and oversees the manufacture of the wheelchair. The project goes back 10 years, but with his work it has advanced to user testing in Minneapolis and Palo Alto, Calif.

“That’s the major reason I’m here. I saw that technology and wanted to be part of it,” said Davis, who previously worked as a project engineer with Stratasys, which makes 3D printers. The standing wheelchair includes 3D-printed parts. If successful, it too could be licensed for commercial production.

Along with the 3D lab, Davis works in the machine shop. “We’re more of a hacker space. It’s a really cool job, the culmination of my career experience,” he said.

He also supports the design engineers with TTAP — the VA Technology Transfer Program.

“TTAP is for ideas, devices and therapies that come from anyone in the VA network who wants to develop them. We will apply our experience and skills to help get the idea through industrial design, functional design and design for manufacturing,” he said.

Davis’ engineering technology degree included an emphasis in plastics. Seventeen years ago, 3D printing was fairly new technology, but he saw its potential. Once, he was two hours late for a date with his future wife, Jillian McDowell Davis, a 2005 alum, when he lost track of time while 3D-printing in a lab.

For his senior capstone, he was the only person who 3D-printed his project — a crank arm for a bicycle pedal. His career in engineering and 3D printing has been cycling forward ever since.